Why are chronic infections with H. influenzae so common?

As Haemophilus influenzae is completely adapted to survival in the human respiratory tract that is its only niche it is essential for this bacterium to be able to adapt to the human immune responses, and to establish itself in niches where it is protected from antimicrobial agents and immune cells such as phagocytes.

In addition to forming biofilms on epithelial surfaces, evidence from resection of e.g. adenoids as well as various infection models indicate that H. influenzae colonize respiratory epithelia intracellularly as well as extracellularly. Additionally, interactions between human cells and the bacteria appear to change depending on which part of the respiratory system is being colonized: When present in the human nasopharynx, H. influenzae do not cause disease and instead adopt a commensal lifestyle as part of the nasopharyngeal microbiome. However, in other parts of the respiratory tract such as the middle ear or the lungs, H. influenzae is known to cause significant inflammation and acute infections

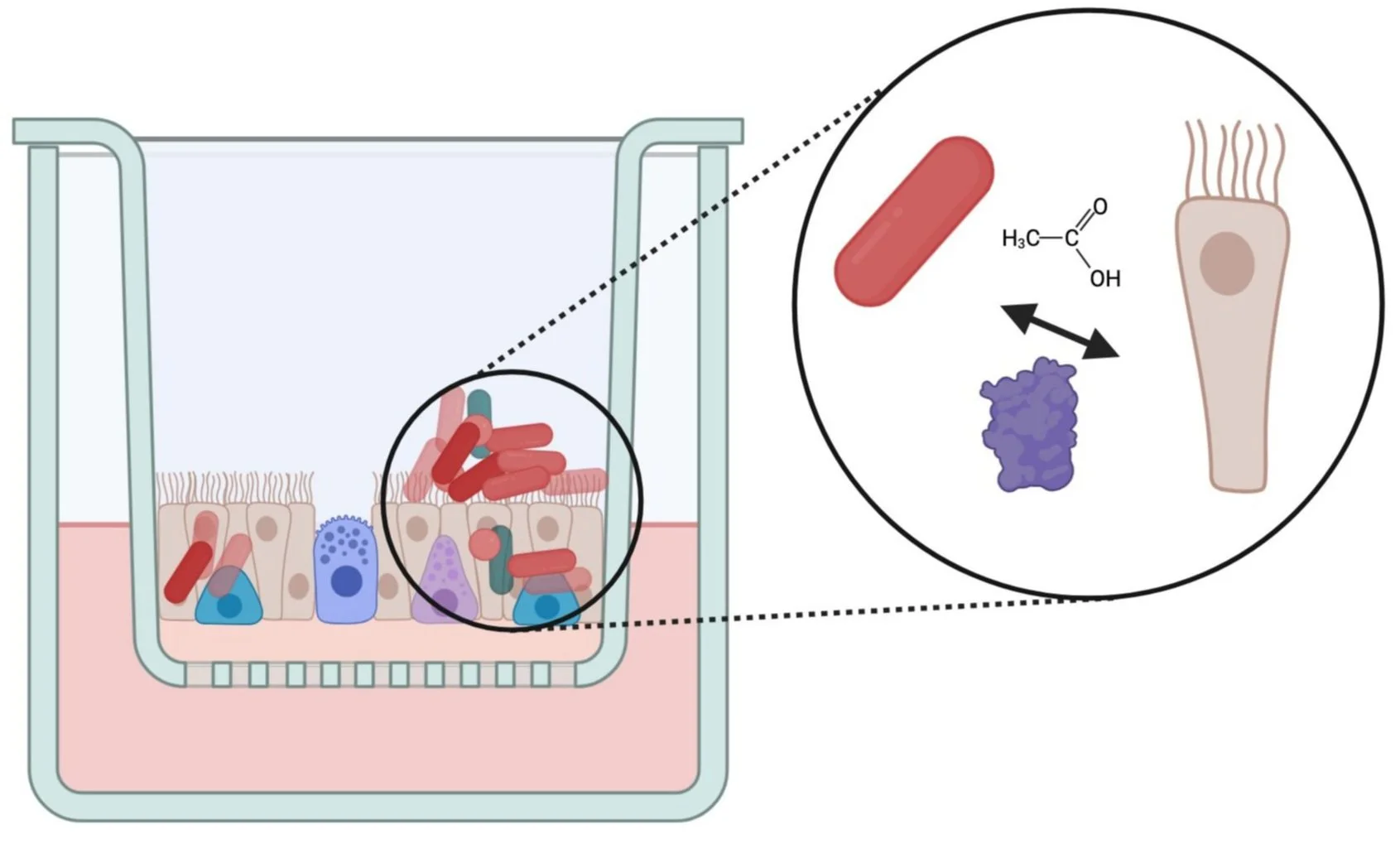

To understand the molecular mechanisms that enable long-term infections we have developed the use of primary human nasal epithelia as the main infection model. The primary epithelia are cultivated at the air-liquid interface (ALI) and contain basal, goblet and ciliated cells, closely recreating the natural niche of H. influenzae.

Using these primary epithelia we have recently shown that H. influenzae quickly established both extra- and intracellularly colonization in epithelia from several unrelated, healthy donors.

Infections with live H. influenzae attenuate the natural immune response of the epithelial cells, indicating the involvement of bacterial metabolite or protein factors in modulating the immune response. The immune response was delayed for ~7 days on average, before slowly being re-established by day 14 (PLoS Pathogens 2024).

Interested? We have student projects available for all our research topics. Please get in touch for more information.

Images created with BioRender

We are currently investigating the molecular mechanisms that underpin these interactions, including the role of immunomodulatory metabolites such as acetate that is a major metabolic endproduct of H. influenzae metabolism affects host-bacteria interactions and the timing and magnitude of immune responses.